Dale L Bumpers, a liberal governor and four-term Democratic senator from Arkansas who came out of retirement in 1999 to make a passionate closing argument defending President Bill Clinton against removal from office in a Senate trial, died on Friday at his home in Little Rock, Ark. He was 90.

Dale L Bumpers, a liberal governor and four-term Democratic senator from Arkansas who came out of retirement in 1999 to make a passionate closing argument defending President Bill Clinton against removal from office in a Senate trial, died on Friday at his home in Little Rock, Ark. He was 90.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PJ1bIgmG3OI

His death was confirmed by his granddaughter Linn Bumpers.

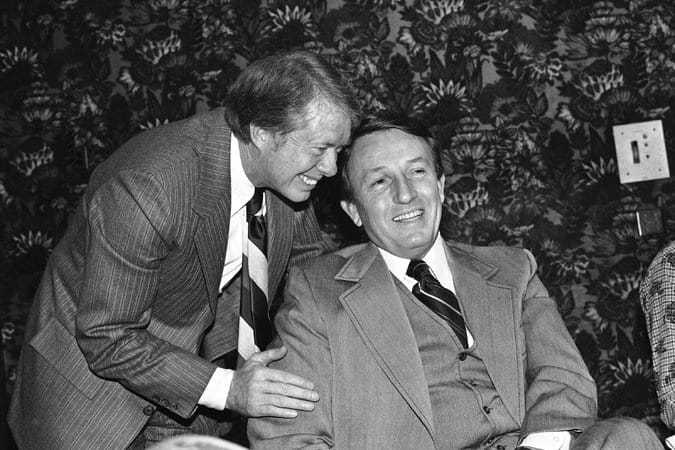

Mr. Bumpers was part of a generation of moderate Southern Democrats, among them President Jimmy Carter, who emerged in the late 1960s and the ’70s. He always said his proudest achievement had come early in his career when, as a small-town lawyer in the 1950s, he guided his native Charleston, Ark., to become the first community of the former Confederacy to integrate its public schools.

But he is remembered more for what he did in the twilight of his career.

Three weeks after retiring from the Senate, he returned on Jan. 21, 1999, to speak to his former colleagues on behalf of Mr. Clinton, a fellow former governor of Arkansas. The House had charged the president with perjury and obstruction of justice for lying under oath about his sexual affair with a White House intern, Monica Lewinsky.

For the Senate trial, Mr. Bumpers was called on to deliver the closing argument for the defense. Before a rapt chamber, he was by turns folksy and self-deprecating, intense and scornful, challenging the House prosecutors who had brought the case to the Senate.

He allowed that the affair was “indefensible, outrageous, unforgivable, shameless,” and that Mr. Clinton had not been forthcoming about it. But lying under oath about sex was not cause for impeachment, much less a conviction, he said: It was “not a breach of the public trust, not a crime against society.”

Mr. Bumpers said that what Mr. Clinton had done, lying about sex, was typical in 80 percent of the hundreds of divorce cases he had tried. It was not, he insisted, what the Constitution’s framers had in mind when they cited “high crimes and misdemeanors” as cause for a president’s removal.

“There is a very big difference in perjury about a marital infidelity in a divorce case and perjury about whether I bought the murder weapon or whether I concealed the murder weapon or not,” he said. “And to charge somebody with the first and punish them as though it were the second stands justice, our sense of justice, on its head. There’s a total lack of proportionality, a total lack of balance, in this thing. The charge and the punishment are totally out of sync.”

In an interview in 2011, Gregory B. Craig, one of Mr. Clinton’s lawyers in the trial, called Mr. Bumpers’s speech “the single most powerful argument in the defense of the president” and “one of the greatest final arguments ever given in an American courtroom.”

A conviction in the Senate was always unlikely; it would have required a two-thirds majority vote, and Democrats held 45 seats. But Senator Tom Daschle of South Dakota, who was the Democratic leader at the time, said in an interview that the Bumpers speech had firmed up the support of Democrats who had been wavering.

Three weeks later, 10 Republicans joined all 45 Democrats to acquit Mr. Clinton on the perjury charge. On the obstruction charge, five Republicans joined the 45 Democrats in voting to acquit.

“For all his country lawyer’s eloquence,” Francis X. Clines wrote in The New York Times after the speech, “the triumph in Dale Bumpers’s extraordinary return to the Senate today was most evident after he finished addressing the chamber he loves so well. For it was then that a remarkably bipartisan crowd of senators — of the very judges and jurors of the impeached President Clinton — hurried to his side in the well of the chamber to shake his hand, to hug him, to congratulate him for a defense lawyer’s job well done.”

Dale Leon Bumpers was born in Charleston on Aug. 12, 1925, to William Rufus Bumpers and the former Lattie Jones. His father and a partner owned the Charleston Hardware and Funeral Home. Deeply interested in Democratic politics, a frequent supper table topic of conversation, the elder Mr. Bumpers served one term in the Arkansas House of Representatives.

Dale Bumpers went to public school in Charleston and enlisted in the Marine Corps in 1943. He was on a ship heading for combat in the Pacific when World War II ended in 1945; he was discharged the next year. He graduated from the University of Arkansas in 1948 and Northwestern University Law School in 1951. While he was in law school, his parents died in a car crash, and he married his longtime girlfriend, Betty Lou Flanagan, an elementary-school teacher.

Returning with his wife to Charleston — population 968 in 1950 — he ran the hardware store and opened the town’s only law practice, which provided the title of his 2003 memoir, “The Best Lawyer in a One-Lawyer Town.”

He was just 28 when the local school board asked him what it should do after the Supreme Court handed down its landmark school-desegregation decision in Brown v. Board of Education on May 17, 1954.

Though the town was not facing a lawsuit on the issue, he wrote, “I told the board and the superintendent, Woody Haynes, that integrating now would be infinitely preferable to waiting for the national chaos that was sure to come.”

The board took his advice: Its five members voted unanimously to integrate, knowing as well that the town would save money by closing a black elementary school and no longer having to bus black high school students 24 miles to Fort Smith.

The reaction in town, Mr. Bumpers wrote, was “amazingly tepid.” On Aug. 23, 1954, 13 black students “walked unmolested, and virtually unnoticed, into the elementary and high schools” of Charleston. (Fayetteville, Ark., integrated its high school three weeks later, and it took the 101st Airborne Division to integrate Little Rock’s Central High School in 1957.)

Charleston’s action attracted little outside notice at the time, in part because local leaders sought to keep it quiet to avoid inciting protests by segregationists.

“That was probably the most important thing I did in my whole life, not just my political career,” Mr. Bumpers said in an interview for this obituary in 2011.

In 1962, he ran unsuccessfully for the Arkansas House seat his father had held. He ran for governor in 1970 as a moderate Democrat and defeated two giants of Arkansas politics: in a runoff primary, Orval E. Faubus, a former governor attempting a comeback, and in the general election, Winthrop Rockefeller, the state’s first Republican governor since Reconstruction, who was seeking a third term.

Although he entered office knowing little about state government, Mr. Bumpers reorganized it into a cabinet system, expanded community college education and won approval for an increase in the state income tax, which required a three-fourths majority of the legislature that Mr. Rockefeller had failed to win.

During his two terms, Arkansas created a consumer protection division in the attorney general’s office, expanded the state park system, began a prison construction program, adopted a state-supported kindergarten program and provided free textbooks for high school students.

Cal Ledbetter, a professor emeritus of political science at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, said that a 1998 survey of historians and political experts in the state had ranked Mr. Bumpers as its best governor of the 20th century. Mr. Clinton, who served 12 years, ranked third.

Mr. Bumpers’s detractors, however, called him personally bland and politically noncommittal. (He was known for “tortured temporizing over big decisions,” The Times wrote.) Mr. Rockefeller dismissed Mr. Bumpers as “a vaguely pleasant man who had one speech, a shoeshine and a smile.”

But his popularity remained high, and in 1974, he unseated another towering figure in Arkansas politics, Senator J. William Fulbright, in a primary.

In the Senate, he had a liberal voting record and battled, generally without success, against such politically sacrosanct targets as the International Space Station and major military spending items. He conceded in the 2011 interview that his rare legislative successes were “not monumental.”

In defending Mr. Clinton, Mr. Bumpers rallied behind a friend who had achieved the presidency that Mr. Bumpers first dreamed of himself when his father took him to see President Franklin D. Roosevelt campaigning in Arkansas in 1938.

In his memoir, Mr. Bumpers said one reason he had given up the governorship to run against Mr. Fulbright, with whom he had no important disagreements, was to put himself in a position to run for president. But while he tested the waters in 1983 and again in 1987, he never ran, citing the difficulty of raising enough money and the loss of privacy that comes with a candidacy.

He is survived by his wife, Betty, who in the 1980s helped found Peace Links, an organization of women that promoted direct dialogue between American and Soviet citizens. His survivors also include two sons, Brent and William; a daughter, Brooke; and seven grandchildren.

After leaving the Senate, Mr. Bumpers remained in Washington to lead the Center for Defense Information, a military policy research institute, and to practice law. He moved back to Little Rock in 2010.

In 2003, when promoting his memoir at a Washington book signing, he said he wanted his legacy to be that he voted against 38 proposed constitutional amendments — on busing, school prayer, balanced federal budgets and other issues — during his time in the Senate.

“Constitutional amendments are palpable nonsense,” he said, “all crafted for political advantage.”

Source: NYTimes

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KtF_4VTDGbw