Samuel DuBois Cook, a lifelong educator who was widely saluted as the first tenure-track black professor appointed by a predominantly white university in the South since Reconstruction, died on May 29 at his home in Atlanta. A boyhood friend of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., he was 88.

Samuel DuBois Cook, a lifelong educator who was widely saluted as the first tenure-track black professor appointed by a predominantly white university in the South since Reconstruction, died on May 29 at his home in Atlanta. A boyhood friend of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., he was 88.

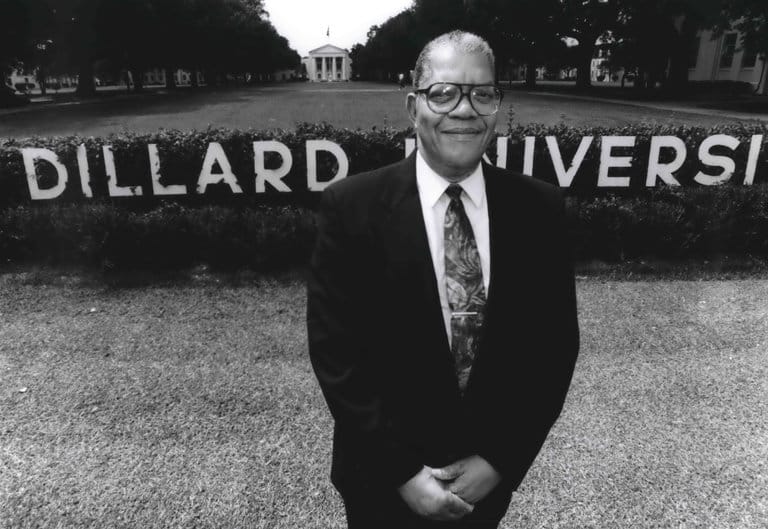

His death was announced by Duke University, where he taught political science from 1966 to 1974 before serving 22 years as president of Dillard University, a historically black institution in New Orleans. No cause of death was given.

If there were any doubts about how the first full-time black professor would fare at a Southern university whose student body had only just been integrated, they were quickly dispelled. By Dr. Cook’s second year of teaching at Duke, in Durham, N.C., his students presented him with their outstanding professor award.

In 1973, he also became the first black president of the Southern Political Science Association. President Jimmy Carter later named him to the National Council on the Humanities.

A political scientist by training, Dr. Cook was a staunch defender of all-black colleges and a crusader for interracial harmony, especially between blacks and Jews.

At Dillard, he established the National Center for Black-Jewish Relations. He also increased student enrollment by 50 percent and started a Japanese-language curriculum.

Dr. Cook was born on Nov. 21, 1928, in Griffin, Ga., a city in metropolitan Atlanta. (His middle name was a tribute to Charles DuBois Hubert, a former president of the historically black Morehouse College in Atlanta.) His father, the Rev. Marcus Emanuel Cook, was a Baptist minister. His mother was the former Mary Beatrice Daniel.

The summer after high school, Samuel Cook and his friend Martin Luther King Jr. were sent by their fathers, both preachers, to work in Connecticut’s tobacco fields to earn money for college. That fall, as precocious 15-year-old freshmen, they entered Morehouse under an early-admissions program aimed at filling classrooms emptied by students drafted for World War II.

Dr. Cook is survived by his wife, the former Sylvia Fields; their children, Samuel Jr. and Karen J. Cook; and two grandchildren.

In 1948, he graduated with a bachelor’s degree in history from Morehouse, where he was student body president and founded the campus chapter of the N.A.A.C.P.

He earned a master’s (in political science) and a doctorate from Ohio State University. He taught at Southern University, in Baton Rouge, La.; Atlanta University; the University of Illinois; and the University of California, Los Angeles, before Duke hired him as an assistant professor of political science. His legacy there includes the Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity.

“I think there is a profound sense in which he was a key architect of the analysis of the impact of race in post-World War II Southern politics,” said William A. Darity Jr., the Samuel DuBois Cook professor of public policy at Duke. “In his work, he fully anticipated the rise of Republican Party in the South and the instrumental role played by ‘states’ rights’ as ‘masks for racism.’ ”

Dr. Cook and Dr. King remained in touch over the years. During the Montgomery, Ala., bus boycott in 1956, he struck a hopeful note in a letter that began “Dear M. L.”

“My mind, heart and spirit go out to you and to all the others for heroic efforts in behalf of human dignity and freedom,” the letter said. “Freedom is not a gift but an achievement. Historically and morally speaking, it is the fruit of struggles, tragic failures, tears, sacrifices, and sorrow. Likewise, social changes, if more than accidental occurrences, if constitutive of moral goodness, are products of imaginative constructions and presuppose the will to make the ‘is’ conform to the ‘ought.’ ”

After quoting the philosopher Morris R. Cohen’s “The Meaning of Human History” (1947), Dr. Cook continued:

“The tragic lesson of American Negro history is not so much rooted in the activity of evil spirits but the inactivity of men of good will — in their willingness to yield instead of fulfill. Your activity and that of others similarly located reveal a radical departure, a new orientation.”

About a decade later, Dr. Cook replied more colloquially when asked by black students how to succeed.

“Have a vision,” he replied, “a dream of success, and work like hell.”

Source: The New York Times